“1762Â Â O. Goldsmith Citizen of World I. 49Â Â Nothing is truly elegant but what unites use with beauty.” — Oxford English Dictionary

The idea of elegance was fixed in the vocabulary of the 18th century, but the precise form it took in the decorative arts would have changed much more frequently. A survey of the use of elegant and elegantly in various descriptive phrases and captions in the 1700s leads to the conclusion that it means “artfully decorated,” especially as opposed to plain. Equally it might intend to say “attractively decorated,” granted that what was attractive one season could be embarrassingly out of fashion the next. Handbooks were published to help people write form letters “with elegance,” and half of what is called elegant is speech or writing, but again with the intention of adding attractive decoration, then as now producing an effect called “refined.”

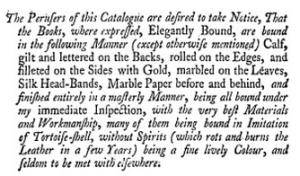

Therefore, we find a range of terminology for states of elegance in booksellers’ catalogues, of which binding is only one, but a very explicit one. The others were understood – finer paper, larger paper (and therefore larger margins), fine or colored illustrations, or specific presses such as the Foulis brothers’ in Glasgow, or Baskerville’s in Birmingham. One might argue that the use of elegant in this context adhered closely to the narrower, literal definition. All of this description also served to explain the prices of certain items in the catalogue. The default binding for any book was plain, and never noted. A note was given if a book was less than bound, that is, still in sheets or boards. Anything more than a plain binding also received a note, and some booksellers offered specific editions in several binding states – even when the least expensive state was well beyond the reach of most of the population. Elegantly bound could mean ordinary calfskin but with gilt tooling, or luxurious goatskin in the gemlike hues of ruby, sapphire, or emerald, or russia calfskin with gold tooling. Additional attractive features such as marbled endpapers, or marbled or gilt page edges, were encompassed in “elegantly bound,” but only the latter would be noted. The majority of uses of this marker received no elaboration, and prospective buyers must have known that elegant implied both decoration and a finer class of leather, as well as a restrained decorative style, in keeping with Dr. Johnson’s definition of elegance, “…beauty of art, rather soothing than striking.” A more thorough analysis of the descriptive terminology in these catalogues is needed not just to grasp what their readers understood by elegant, but also to shed light on what was ordinary, plain, and unstated.

It may be worth noting that buying books in 18th century London does not compare to buying books today. It compares more closely to what we experience when buying cars, both in terms of expense, and selection, and the range between affordable and luxury. If we can imagine not being able to pay for a car over a three year period. An elegantly bound book might be said to be comparable to a BMW or Mercedes. Anything more (goatskin, all edges gilt) would be a Bentley or a Jaguar. A Baskerville might be a Tesla.